Related Pages

At a glance

Understanding trauma's affect on the brain

When people experience trauma, their physical and emotional survival and wellbeing are under threat, and they are overwhelmed by feelings of fear and terror. Our minds and bodies have evolved over thousands of years so that we can survive and protect ourselves from these dangers.

Ways of Coping

The most common ways of coping are:

Fight – Our bodies automatically prepare to fight.

Flight – Our bodies automatically prepare to run away, by releasing adrenaline.

Freeze – When fight or flight are not an option, the body will freeze, rather like a rabbit in the headlights of a car. The body is unable to move

FRIENDS/Submission – We may go passive or complaint, do things to appease, not say anything or make themselves as insignificant as possible to survive the trauma and stop it happening. This can include supressing our own needs and desires to please others or avoid conflict.

FLOP/Dissociation – This happens when people shut off from their feelings. They can sometimes feel as if they are outside their bodies and numb to their emotions. It can also include extreme tiredness or fainting.

These responses are automatic and under our conscious control. They are the brain’s hardwired responses for survival. Some people can become critical of how they coped during a traumatic event and feel they should have acted differently. They may even believe that they are to blame. For example, it is common for a person who is sexually assaulted to freeze, and be unable to fight back or run away.

Remember, nobody choses how they respond to trauma. In fact, your brain sets off a process for your body to go into an automatic response in order to help you survive. Survival is the overriding goal.

Trauma and the brain

It is useful to understand a bit about how the brain and body react to trauma. This will give an understanding of how people may respond to trauma.

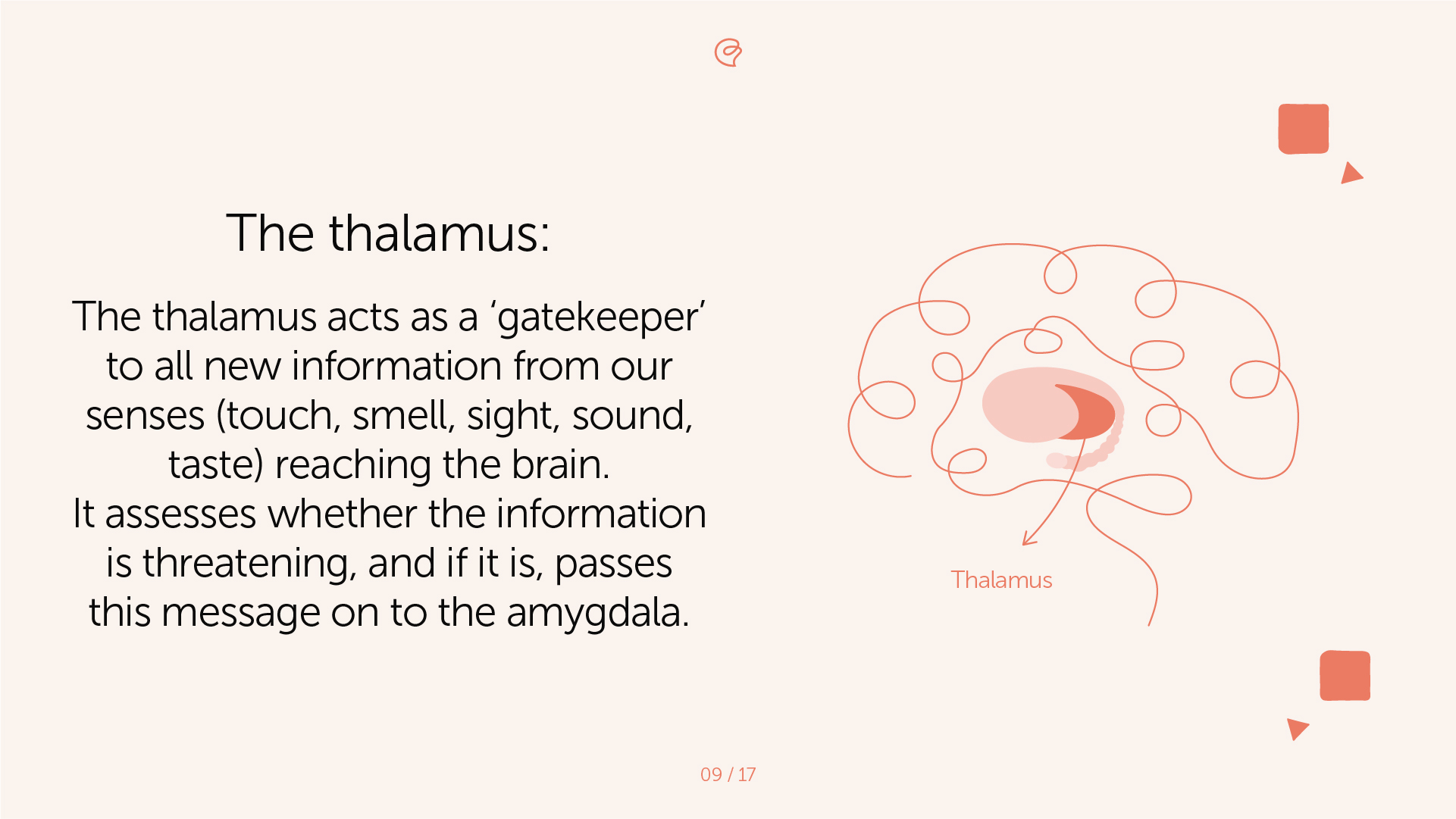

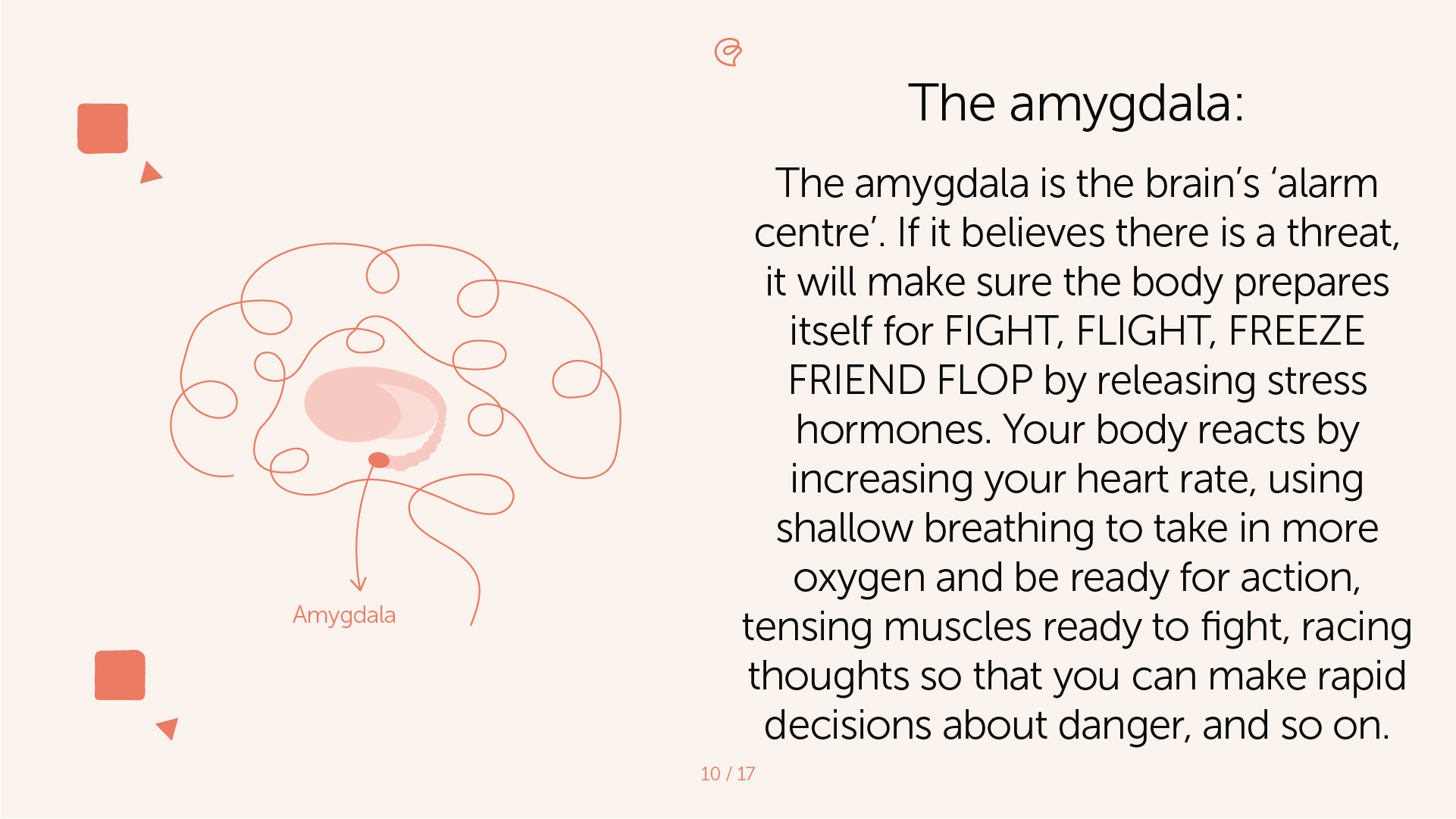

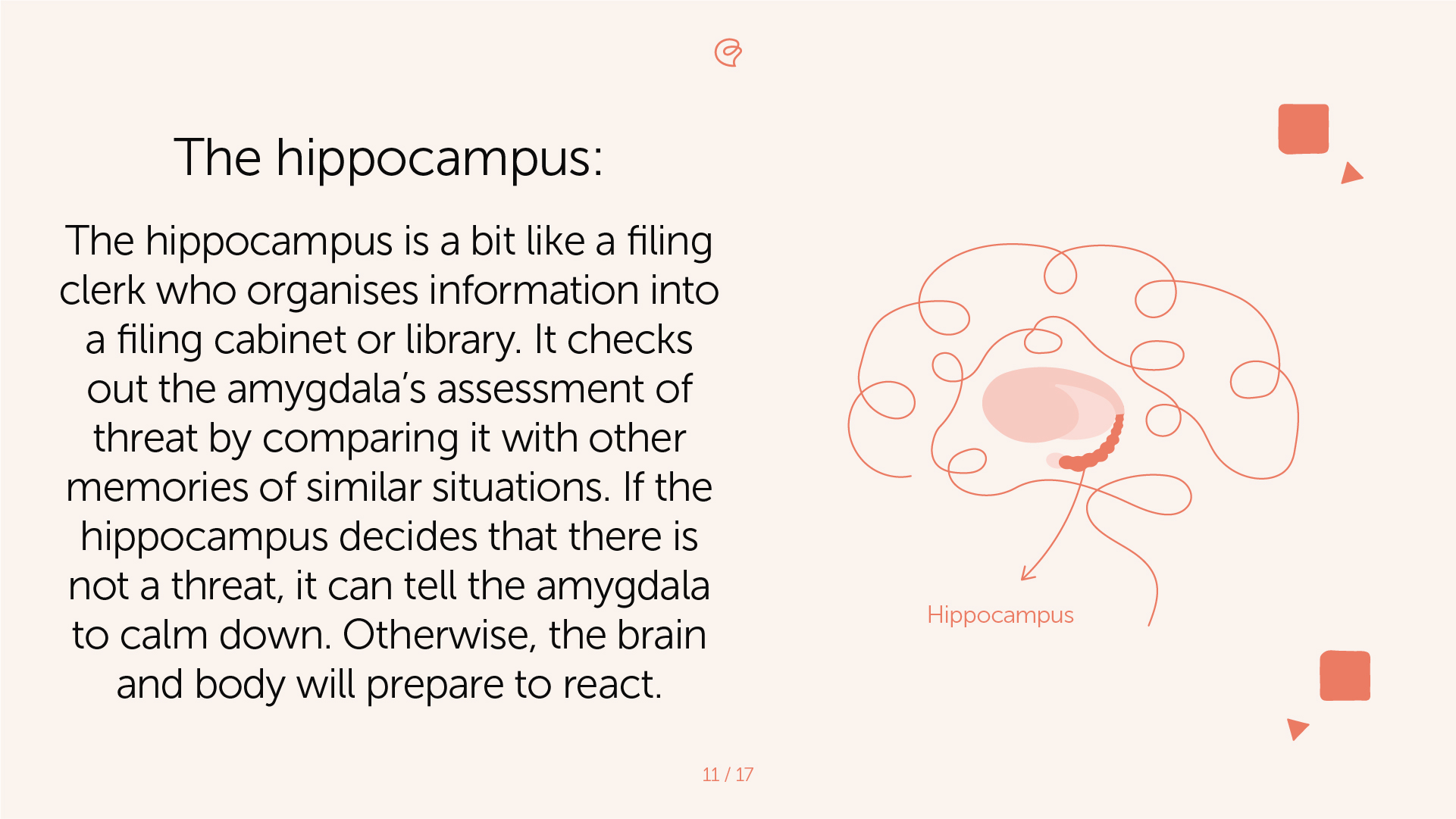

The main areas of the brain that deal with threat are the thalamus, the amygdala, and hippocampus:

- The thalamus acts as a ‘gatekeeper’ to all new information reaching the brain. It assesses whether the information is threatening, and if it is, passes this message on to the amygdala.

- The amygdala is the brain’s ‘alarm centre’. If it believes there is a threat, it will make sure the body prepares itself to fight, flee, submit, freeze or dissociate by releasing stress hormones. Your body reacts by increasing your heart rate, using shallow breathing to take in more oxygen and be ready for action, tensing muscles ready to fight, racing thoughts so that you can make rapid decisions about danger, and so on.

- The hippocampus is a bit like a filing clerk who organises information into a filing cabinet. It checks out the amygdala’s assessment of threat by comparing it with other memories of similar situations. If the hippocampus decides that there is not a threat, it can tell the amygdala to calm down. Otherwise, the brain and body will prepare to react.

Another important part of the brain is the Pre-frontal Cortex – this is the thinking and reasoning part of the brain. During a traumatic event this part of the brain gets bypassed or ‘shut down’ to focus on survival. This is why may people report not being able to think clearly or think at all.

However, in people who have experienced extreme or long-lasting trauma, the amygdala (alarm centre) can become over-reactive. It has a ‘better safe than sorry’ rule which means that it sometimes reacts to small triggers as if they were serious dangers. In people who have experienced trauma, the amygdala becomes hyperalert to all sources of potential threat, even when there is no actual danger in the present moment.

Another factor is that trauma memories are processed in a different way and stored in a different part of the brain from ordinary everyday memories. The hippocampus acts like a filing cabinet for storing memories. Usually, the hippocampus labels memories with dates and places, such as ‘This happened 3 years ago, when I was out for a walk near my home.’ But trauma memories are not as easily stored, and not filed away properly as they should. This is because during times of great stress, like a trauma event, the amygdala will activate with a sole purpose of helping us to survive. While this survival response is happening, it can have the effect of switching the hippocampus (the filing system) offline so that it is no longer able to take in the information it needs to process what is happening properly.

This means that after the event, the memory of the incident is often experienced as confused, disjointed and associated with strong feelings such as fear or anger. The memory may jump into your mind at unexpected times.

When a memory of the traumatic event is triggered, the amygdala treats it as if the event is happening right here and now because the hippocampus does not have the information it needs to properly assess the triggering information and switch the alarm off (amygdala).

This means the amygdala interprets the triggering information as threat and leads you to believe you are in just as much danger in the present moment as you were in the past when the trauma happened. Stress hormones are released, and you may feel terrified and hyperalert, or else frozen and numb just like the time of the actual trauma event, even though that time has passed.